Read

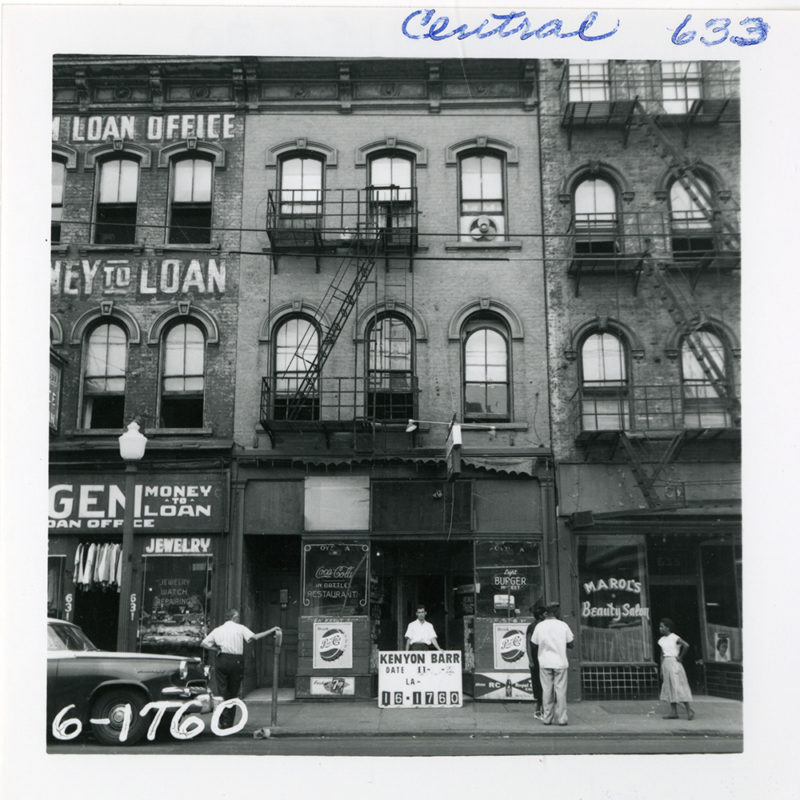

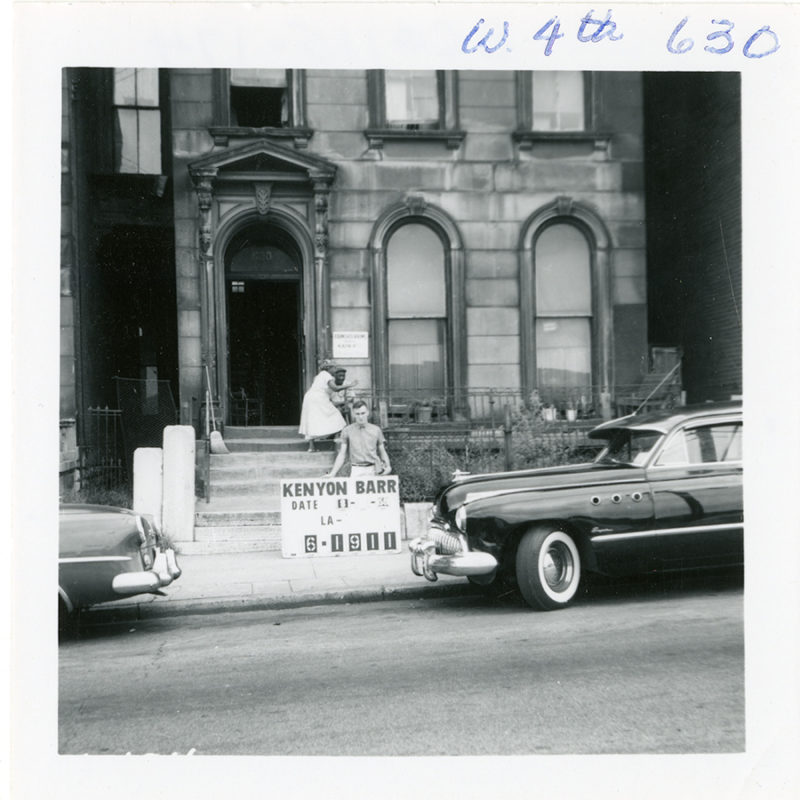

633 Central. 1959. Structure at 633 Central. Kenyon Barr project # 16-1760. First floor occupied by Roy’s Bar and Grill. Kenyon Barr Collection (SC#115-494). Cincinnati Museum Center History Library and Archives.

Acknowledgements

I wish to acknowledge the ancestors whose blood, sweat and tears “brought us thus far on the way,” as well as my mom and dad, who gave me a heart for people; my wife Regina, who gives me stability; and my three beautiful children, Damon IV, Eric Charles and British Cristal, who are my inspiration to never give up.

I also wish to acknowledge my New Prospect Baptist Church family, who loves me unconditionally; Myki Bobo, my trusted assistant; and Iris Roley, my partner in all things “Black.”

Peter Block and Barbara Lyghtel Rohrer deserve my thanks for believing that I had something worth hearing. And I thank my Community Economic Advancement Initiative (CEAI) family and my Collective Empowerment Group (CEG) family. Both are vehicles for substantive change. And a big thank you goes to the publisher, Restore Commons.

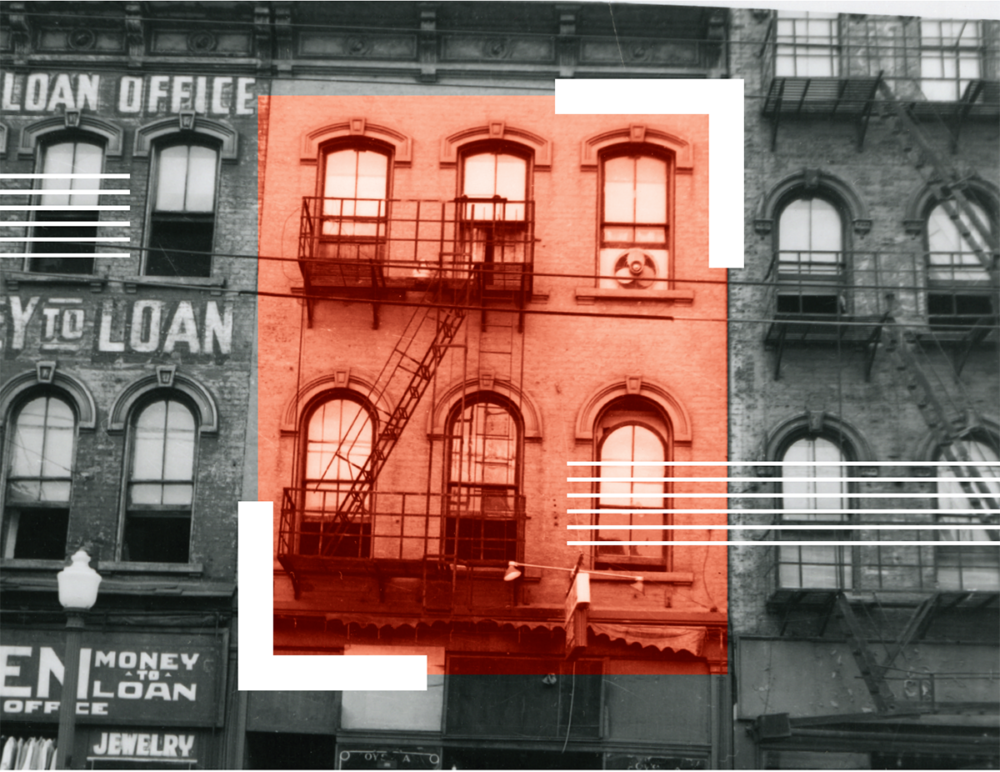

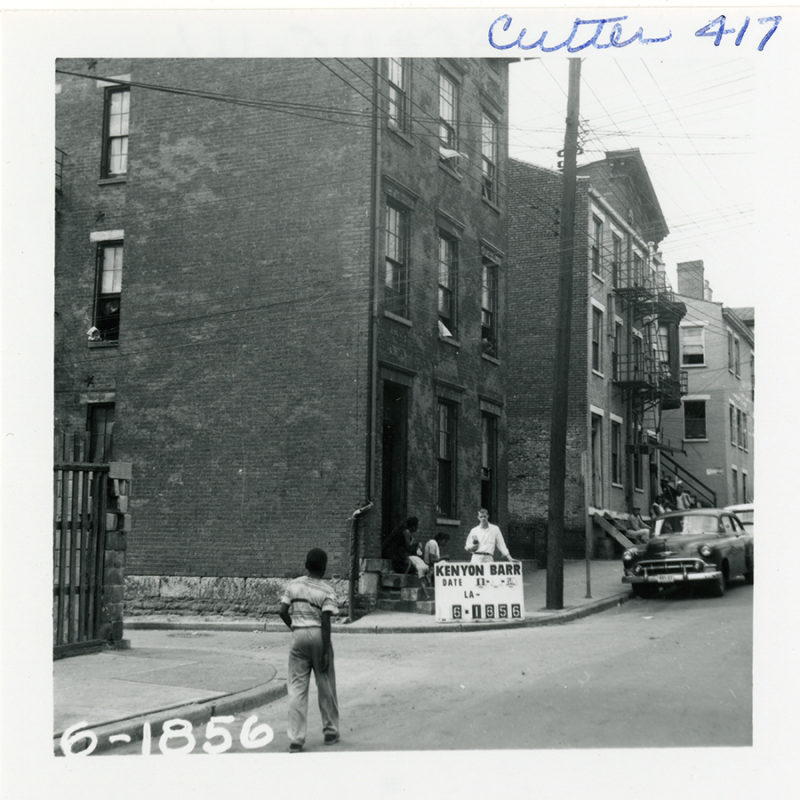

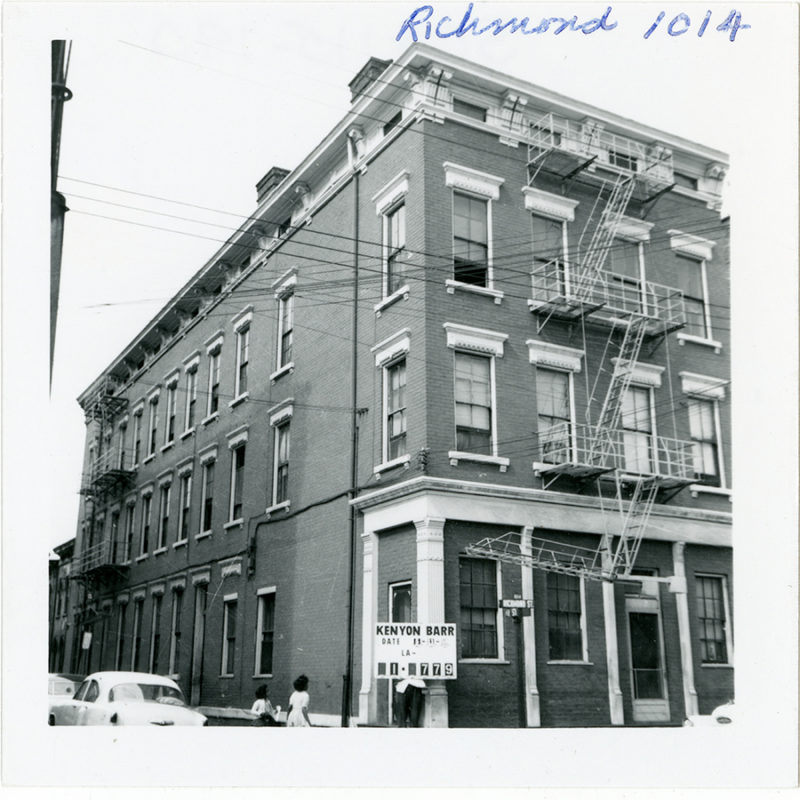

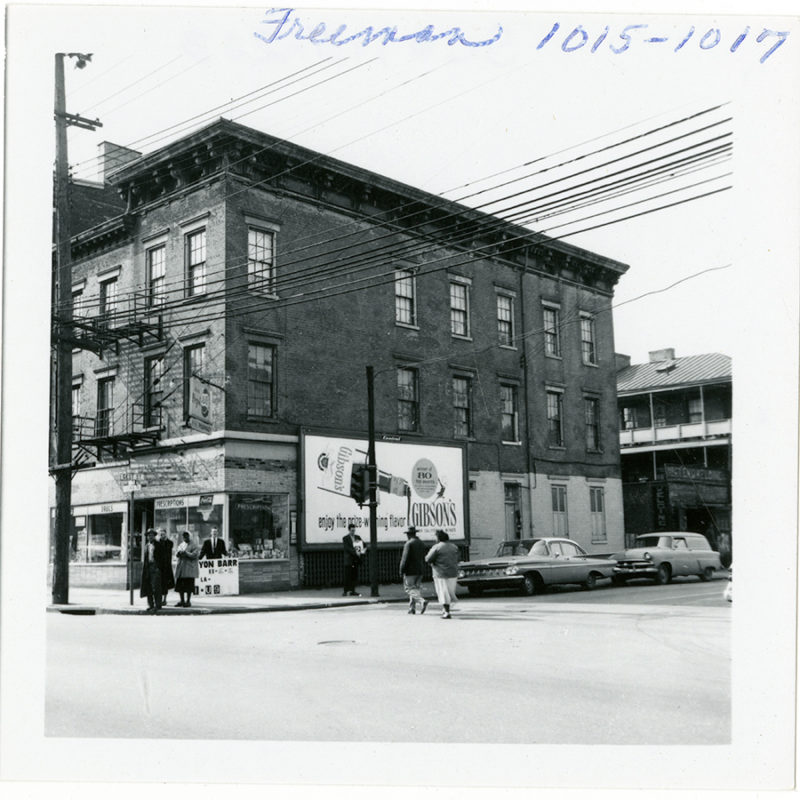

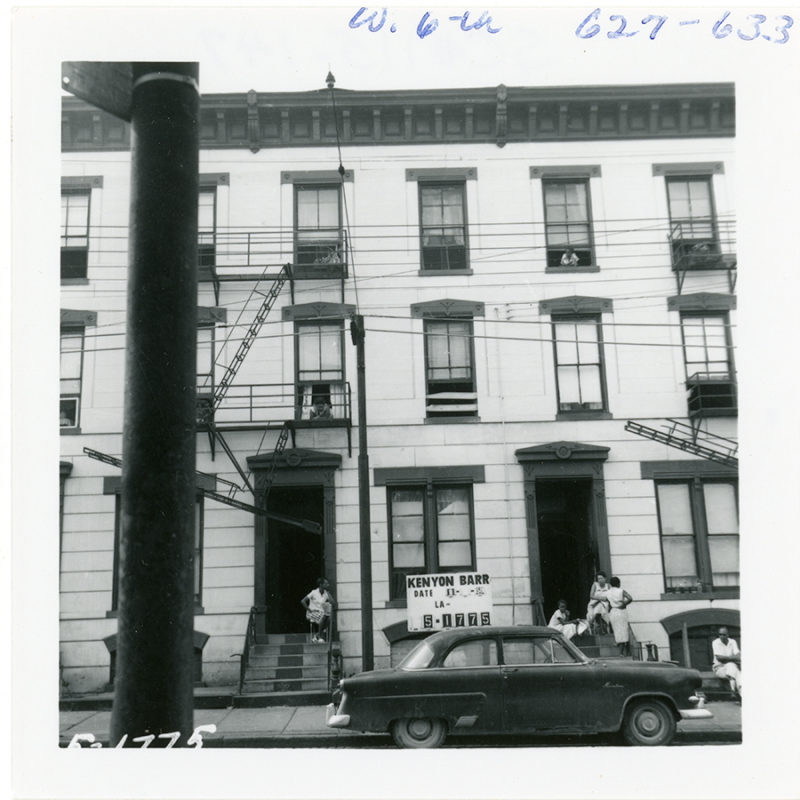

I also want to thank the Cincinnati Museum Center for use of the images published here. The photos are from Cincinnati’s Kenyon Barr neighborhood in the 1950s, a thriving Black community of 26,000 people until the city took the land for an industrial complex that never materialized. Before the people were scattered and their homes and businesses torn down, the city photographed it all. The photos on these pages are from that collection.

Finally, thank you to my mentor and friend John McKnight, who taught me about the importance of “gifts” and their power to unleash community transformation.

This booklet is an edited collection of my thoughts, sermons, speeches and writings that reflect my more than 40 years of community experience and activism. I doubt if anything you read will be particularly groundbreaking, but I hope it will be motivating and actionable.

The work of community building is second only to “soul saving.” True community is made up of loving, affirming families, thriving economic opportunities and a deep sense of justice and equity for all.

May God Bless You All.

Damon Lynch III

Introduction

I first met the Rev. Damon Lynch III when I interviewed him for a church publication. That was in 2016. Since then our paths have crossed a couple of other times. And each time I heard him speak, I became all the more impressed with the man. So when Peter Block, a citizen of Cincinnati whose focus is community building and civic engagement, asked me to collect and then edit the words from Lynch’s talks of recent years into a single document, I was more than pleased to take up the task.

Block has been working with Lynch for years, primarily for economic justice. Economic injustice can be found at the heart of much racial injustice. Block wanted a formal document that could be easily circulated to serve as an additional catalyst for a movement to change such systemic inequity. Through this work, Lynch has come to see his role within the Black community shifting from that of a Moses to a Joshua. He calls for African Americans to claim their destiny, much in the way that God commanded Joshua to take the Promised Land: “Be strong and brave. You will lead these people [to] take the land as their very own. It is the land I promised … long ago.” (Joshua 1:6)

This shift in roles for Lynch is not so much a change as it is an extension of what he has always done. He shares a story of how a childhood friend told his mother that he and Lynch had reconnected.

“Damon was your protector,” she said to her son. “He always watched out for you at school.”

When the friend relayed this conversation to his old friend, Lynch was surprised.

“I didn’t know anybody knew that,” he said, “but that’s what I have always done. I didn’t like seeing other people bullied. I’ve always stood up for people who needed somebody to stand with them or for them. I don’t know why.”

I suspect the reason is deeply rooted in his faith and a clear call from God. Lynch answered that call by becoming a minister. But he is equally a visionary activist, a biblical scholar and a prophetic voice in a time crying for such a voice.

In the following pages, Lynch outlines what he sees as the way forward for the Black community to become thriving, successful, healthy and whole.

This is his road map.

Barbara Lyghtel Rohrer

Editor | Winter 2021

I. BUILDING ON SCRIPTURE

The Truth Will Set Us Free

“And you shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free.”

When I read the Bible, I read it as the living Word of God. I see it as a launching pad for what the God of Israel has done and can still do. In Genesis 15:13-14, we find God talking to Abraham: “Know for certain that your descendants will live as strangers in a land that is not theirs, and they will be enslaved and mistreated for 400 years. But I will judge the nation that they serve, and afterward they will come out with great possessions.”

It has now been just more than 400 years since the first Africans were brought as slaves to our North American shores. I believe that as 2019 closed, we ushered in the time of “true emancipation” for the descendants of those slaves and the millions who followed. We have asked God for what theologians call “a dual fulfillment of prophecy,” for God to do for African Americans as God has done for the children of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, and that is to end 400 years of oppression. It is now a time for great possessions.

I pray this may be so. I preach this may be so. I believe this will be so.

I think too often in the Black community, we’re stuck in the Moses narrative with people thinking they need to be delivered. Indeed, I spent most of my life believing that I was to be a Moses to my people, delivering African Americans from bondage just as Moses led his people out of bondage.

Because of the work of a twentieth century crop of courageous individuals such as the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, Fannie Lou Hamer, Ella Baker, Rosa Parks, Medgar Evers, the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth and Kwame Ture (Stokely Carmichael), that work is now complete. Joshua is the one we need now. Joshua became the leader of the Israelites following the death of Moses. He is the one who led his people into the Promised Land, following God’s command to take the land as their own. Joshua is the man who challenges us to possess the land, to possess the promises. We African Americans need to step into the Joshua narrative where there are opportunities to build wealth, to build sustainability for our Black community and to rebuild our Black families. To do this, we need fortitude and courage.

To those who say, “I don’t know, Damon. I don’t know,” I say, “No.” We don’t have another 40 years to walk in circles. God has brought us to the edge of the Promised Land. We need now to possess this promise. We need to claim the blessings of the God that we say we believe in. We are to cross the River Jordan and, as a people, possess the land.

The Bible said that John the Baptist was a voice crying in the wilderness. I heard a great preacher once say, “It was a voice crying in the wilderness at a time when the wilderness was crying for a voice.” Jesus was the voice the wilderness was crying for then. And now, again, there is a voice crying in the wilderness. My Black brothers and sisters, it is the voice of our ancestors. It is the voice of the enslaved and oppressed. And the wilderness that is this country is crying for a voice. The voice that our nation is crying for is our own.

So, I ask God to do for us and with us what God did for the children of Israel. In order for God to answer this prayer, we need to step forward. And the time to do so is now.

This is actually a lesson I learned from my Jewish friends. They once asked me if I knew why there was a Jewish Hospital in Cincinnati. I did not know.

“We built Jewish Hospital because there was a time when other hospitals would not allow our Jewish doctors to practice,” they said. Once built, they did not call it the Burnet Avenue Hospital. Nor did they call it the Avondale Hospital, either of which was something the Black community may have been tempted to do, criticized as they would have been if they called it the Black Hospital. No, the Jews that built that hospital proudly named it after their community. They called it Jewish Hospital with a sense of pride and a sense of ownership.

Too often, when African Americans try to gain the same advantages offered to white people, we are accused of reverse racism. My Jewish friends answer to that: “Damon, forget what they say. Build your community.”

Repairing the Damage

“Revolution is based on land. Land is the basis of all independence. Land is the basis of freedom, justice and equality.”

The parallel between the biblical text and the plight of African Americans is striking. And just as God made a promise to the Israelites in ancient times to repair the breach— repair the damage — the same promise is to be true for the Black community if we believe we deserve it.

There is a very real and very serious effect from more than 350 years of slavery and Jim Crow, and that is the negative impact on the psyche of most African Americans. It is an overriding sense of inferiority that maybe not all but most African Americans live with. We wake up with it every day, while white Americans wake up to white privilege that most don’t even acknowledge. White Americans never doubt their place in our society, while we who are Black are continually trying to fit in, trying to belong — asking what do we deserve?

That is the damage that needs to be repaired. It is the damage done to an enslaved and mistreated race of people for hundreds of years. Following slavery and Jim Crow (as close to another name for slavery as you can get), we had 50 years of mass incarceration, which has devastated our Black community. And more. Our nation has been devastated. And such devastation calls for reparations.

How do we reply to those who say since slavery no longer exists, there is no need for reparations? It is true that slavery was abolished in this land more than 150 years ago. But reparations are still needed, both from the legacy of slavery and the wrongs that continue to be done to African Americans today.

In the Bible we find God’s promise to repair the damage. Yet, to bring about this reparation, we need to believe this is a work that we truly deserve. We can demonstrate this belief by repairing the damage done in recent generations. We can repair our families, establish our financial security and build our community.

This is God’s vision for us. This is God’s promise to us.

II. SLAVERY BY ANOTHER NAME

Too Prosperous to Be a Negro

“I would like to be known as a person who is concerned about freedom and equality and justice and prosperity for all people.”

The period following the Civil War was one of economic terror. One story that I tell is of Elmore Bolling, a successful small businessman who lived in Alabama in the middle of the last century.

Bolling leased a plantation where he had a general store, a gas station and a catering business. He was a one-man economy. He grew cotton, corn and sugarcane. He also operated a small fleet of trucks that ran livestock and made deliveries between Lowndesboro and Montgomery. At his peak, he employed as many as 40 people, all of them Black.

One December day in 1947, a group of white men showed up along a stretch of Highway 80 that Bolling helped lay. There, near his store and home, where he lived with his wife Bertha Mae and their seven children, the men shot him eight times. His family rushed from the store to find him lying dead in a ditch.

The shooters did not even cover their faces; they didn’t need to. Everyone knew who had done it and why.

“He was too prosperous to be a Negro,” someone who knew Bolling at the time told a newspaper.

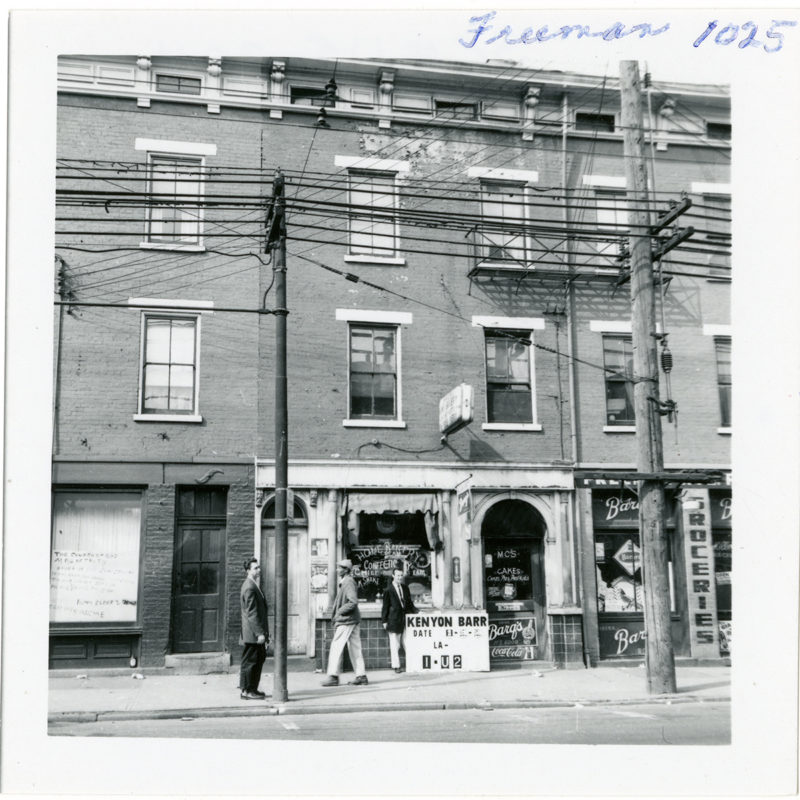

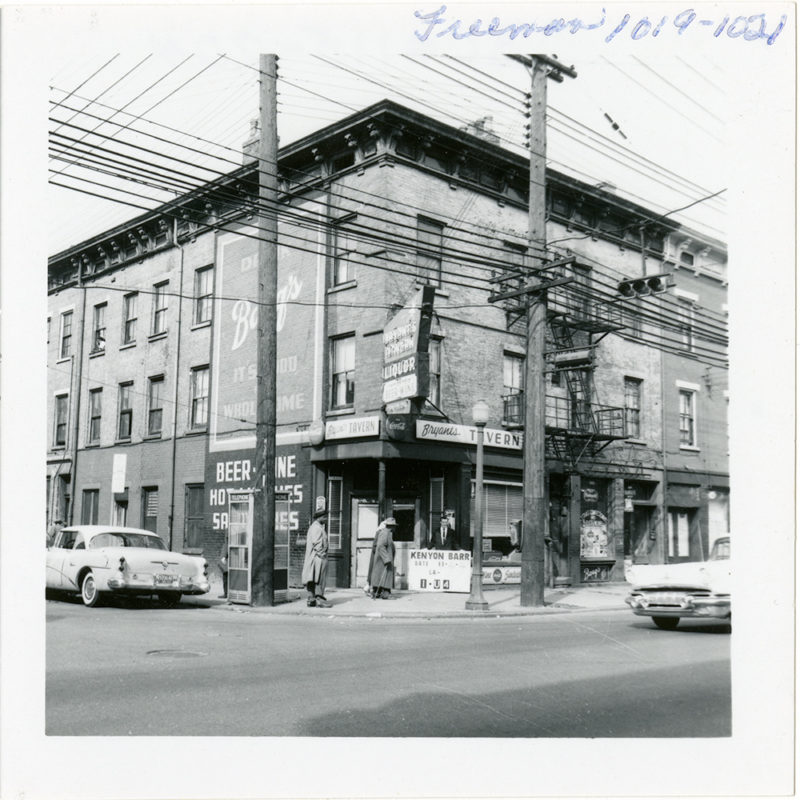

Kenyon Barr project # 1-U2. Kenyon Barr Collection (SC#115-901). Cincinnati Museum Center History Library and Archives.

When Bolling was killed, his family estimates he had as much as $40,000 in the bank and more than $5,000 in assets, about $500,000 in today’s dollars. But within months of his murder nearly all of it would be gone. White creditors and people posing as creditors took the money the family got from the sale of their trucks and cattle. They even staked claims on what was left of the family’s savings. Overnight the Bollings went from prosperity to poverty. Bertha Mae found work at a dry cleaner. The older children dropped out of school to help support the family. Within two years, all the Bollings fled the county, fearing for their lives. Left behind were Bolling’s employees who had also lost their livelihood and the means to support their own families.1

Such wealth-stripping has left African Americans at a lasting economic disadvantage. Redlining, which began with the National Housing Act of 1934 and continues to this day, is a form of lending discrimination.

Banks and insurance companies “fenced off” areas where they could avoid investments based on demographics. This practice left far too many Black communities underdeveloped and in disrepair. It also hindered African Americans from the wealth building prospects of home ownership and business development.2 In fact, while African Americans were fighting for freedom and basic human rights, white Americans were building generational wealth, industries and institutions.

Today, the typical white family has a net worth ten times higher than the typical Black family.3 The median family wealth for white people is $175,000, compared with just $17,000 for Black individuals. According to the Economic Policy Institute, more than one quarter of Black households have zero or negative worth. Even worse, Black wealth in America is not going up; it’s going down.4 If this trajectory continues, by the year 2053 Black median wealth in America will be zero.

According to Forbes, the top 400 richest Americans have more wealth than the entire Black population and a quarter of the Latino population combined.5

We people of color have been part of this land of the free for more than 400 years now. Our experience as Black Americans is not the same as that of white Americans.

White people who want to join the struggle for justice for all Americans say they don’t know what it is like to be Black. I find that interesting because, as a Black man, I do understand white people. I have what W. E. B. Du Bois called a dual stream of consciousness. I have an Afrocentric stream, and I have a Eurocentric stream. Upon seeing Rodney King being beaten by police on television, Black America asked, “Why did they just keep beating him?” while white America asked, “Why didn’t he just lie down?” We’re looking at the same thing but seeing different things. When the verdict was announced following the O. J. Simpson trial, white America was dumbfounded and said, he is guilty, while Black America said, yes, he got off. When Timothy Thomas was shot in Cincinnati, the majority of Black Cincinnati asked, “Why did they shoot him?” White Cincinnati asked, “Why did he run?”

The first three Gospels, the books of Matthew, Mark and Luke, are called the Synoptic Gospels. Synoptic comes from the Greek for “stands with vision” or “together view,” meaning that in order to see the same things, we need to be looking through the same lens. I grew up immersed in the white culture, so I can see “just lie down,” “he is guilty” and “don’t run.” But I know white people do not have my lens and cannot see what I see.

Likewise, when white people come forward to help in the struggle, they don’t understand that any effort they contribute is not just to help Black people. It is to help our nation. It is to heal our nation.

Kenyon Barr project # 1-U4. Kenyon Barr Collection (SC#115-894). Cincinnati Museum Center History Library and Archives.

A Stolen History

“A people without the knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots.”

The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks, by Randall Robinson, traces the lineage of a Black male living in contemporary America, a representative individual. I summarize Robinson’s illustration.6

The great, great grandfather of today’s Black male was born a slave and died a slave. His labors enriched both his white Southern owners and the owners of Northern businesses who depended on the cotton trade. He was taken from his mother and father and sold as a little boy to a slave holder who lived in another state — can you imagine the cruelty of that? He never knew where his people in Africa came from. He was illiterate, by law. Backbreaking work and abuse marked his days.

His son, also born in slavery, was also taken— sold, stolen — from his parents at a young age. This son was a teen when the Civil War ended. The new Black codes that followed, passed throughout the South, meant that his life as a freed man was little different from his days in slavery — Black men who quit their jobs could be jailed. And because he was illiterate, this son had little means to make a fresh start. He picked up work as he could.

His son, born at the turn of the century, did learn to read, but that ability changed little in his life. Facing ongoing racial discrimination, he became a sharecropper, working for white men who once owned his grandfather. He was not able to vote. When he had a son, he wanted more for him, but Southern segregation and its punishing Black codes left little for his family in terms of education, income or freedom. He sank into despair.

His son, the father of today’s Black male, never finished high school. He made his way in the world as a laborer, as did anyone who looked like him. He worked for white people who lived in nice neighborhoods, unlike his neighborhood.

He drank away his hopelessness as his father before him and died of heart disease when he was barely out of middle age.

This is the lineage that has birthed today’s Black male, who is far more likely than his white counterpart to be undereducated, unemployed, imprisoned, in poor health, even murdered.

When four million slaves were freed, nothing was given to them as compensation for their years of brutal labor forced upon them and their families—let alone any kind of national apology.

Robinson goes on to ask what have been the greatest human rights offenses in the last 500 years. Some mention the Holocaust. Others mention Pol Pot, or what happened in Rwanda. Unfortunately, the second half of the past millennium has seen plenty of human rights violations and human massacres. But rarely mentioned is what happened to the Native Americans. And more rare is the person who speaks of the horrors of the slave trade of Africans stolen from their homes and shipped like cargo to the United States for 244 years.7 Add another 100 years of systemic racism on top of that and it is hard to understand why the desecration of the Black body and spirit is not decried as other genocides through history are.

So how do I reply when asked, “Who are those angry Black males in the streets of Ferguson and Baltimore and elsewhere?” I say, “They are the great, great grandsons of that Black man on the plantation who never learned to read. They are the great grandsons of that Black man forced to continue to work as a slave even though he was free. They are the grandsons of that Black man who was denied the right to vote.” It’s damage that probably every Black person in this country feels on a daily basis.

The first Black people who landed on the shores of this country did not come here of their own free will. Instead, they were brought here in 1619 for slave labor — 20 Africans, stolen from their homeland. Their descendants, bought and sold as property, spent the next 244 years fighting to be free. The Emancipation Proclamation, which outlawed slavery in the Confederate States, was signed by President Abraham Lincoln in 1863. But it was not evenly enforced until 1865 when the Union General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas, the most western of the slave states, at the end of the Civil War. (The enforcement of the Emancipation Proclamation was dependent upon the arrival of Union troops.)

From 1619 to 1863, our Black ancestors were simply fighting to be free— and producing some of the most courageous people the world has seen, such as Nat Turner, Denmark Vesey, Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth to name a few. The next 101 years were spent fighting for their God-given rights as human beings with all the respect and dignity that entails. From 1863 to 1964, these former slaves and their descendants were fighting not only to be equal in the sight of the law, but in the hearts of our white brothers and sisters. The struggle continued with the War on Drugs, mass incarceration and ongoing redlining. Racism, discrimination, police brutality, hatred and fear continue to this day. We African Americans can see it. We feel the impact.

A few years ago, my wife and I had dinner at a friend’s house. My friend is Italian and so was the dinner. I loved it —I loved the food. I love that my friend had this great Italian family. I loved that they knew where they came from. And I sat there wishing I knew the same.

It’s not that I don’t have a Black family rooted in the South. No, my longing went deeper than that. Until I started receiving advertisements in the mail encouraging me to buy Irish-themed products, I had no idea that the name Lynch was Irish. How in the world am I Irish? I have no clue as to the African lands my ancestors came from. And I am stuck with this Irish last name that means nothing to me.

The Disappearing Black Neighborhood

“The problem occurs when poorly managed gentrification leads to rocketing price inflation, social disruption and a loss in cultural diversity.”

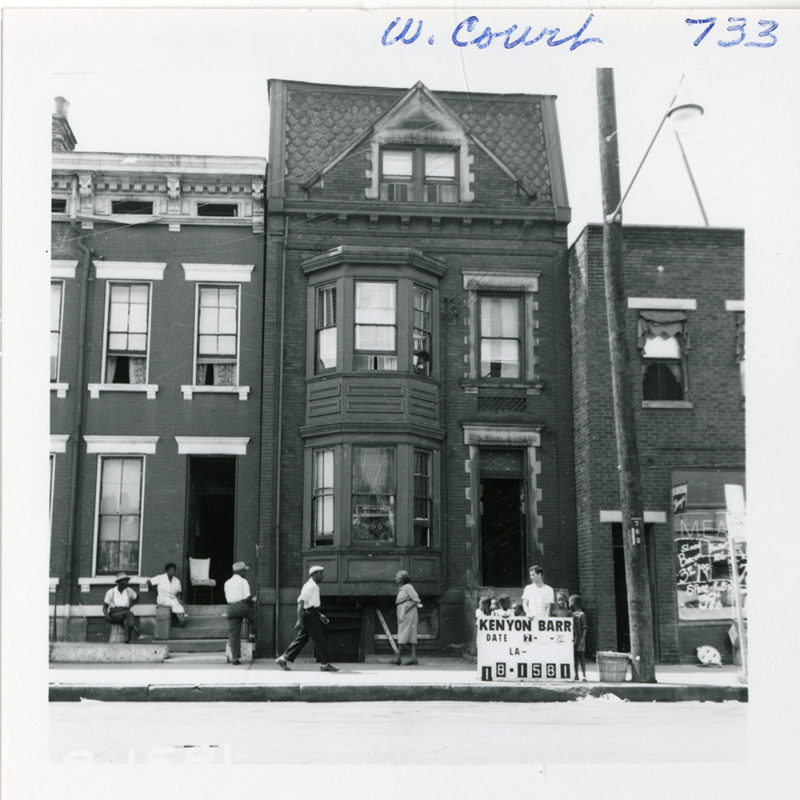

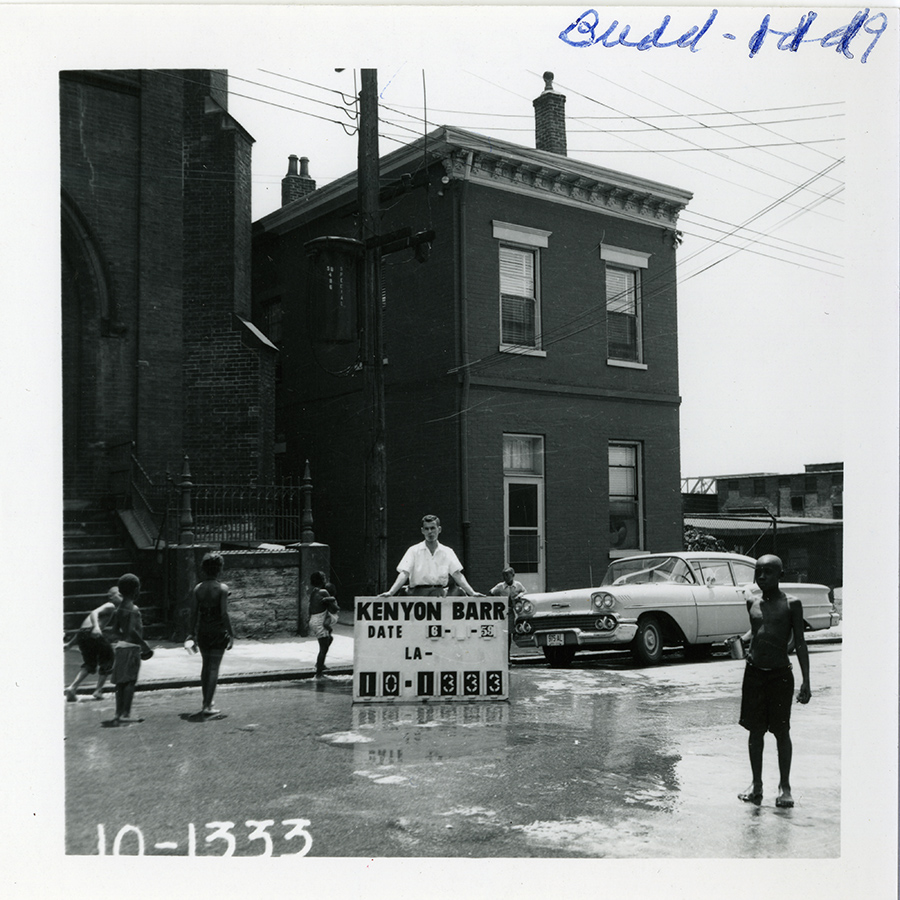

Have you ever heard of Kenyon Barr? Perhaps not. But those living in Cincinnati know Queensgate, part of the city’s West End. That is where Kenyon Barr was.

Kenyon Barr was a vibrant Black community until the city decided to take the land for light industrial development. They cleared the houses. They cleared the shops. Two thousand buildings were destroyed. Twenty-six thousand people were forced to move away, their community destroyed. Before the destruction began, the city went into the neighborhood and took photographs of what they were about to tear down. The photos show people outside their homes and shops engaged in their lives. They had no idea what was about to happen. As for the light industrial development the city envisioned, it never took off.8

When I tell this story, people are surprised and shocked over what the city did to that community. What saddens me is that the people speaking their outrage don’t see that that kind of displacement is still happening. It even happened on my watch. That time it was in the Over-the-Rhine (OTR) neighborhood. That’s where New Prospect Baptist Church, where I serve as senior pastor, was before we outgrew our building and moved into a larger complex, the former Jewish Community Center, in the neighborhood of Roselawn.

In the 26 years that I was in Over-the-Rhine, I watched it transform. I watched it die. We went from 15,700 people to 7,000 people. Then the crime rate rose. Since then, the area has been reborn. Articles in The New York Times and Forbes say that what happened in Over-the-Rhine is a great rebirth, “a grand tale of urban revival.”9 I don’t share that same feeling.

That’s because the people who made their home in OTR were driven out, displaced by the gentry, the people who see something they want and who have the power, money and connection to take it, to make it into a place for themselves without consideration of those who may already be living there. We have a history of that in this country.

I watched every local bar shut down, every laundromat close, in Over-the-Rhine. It was surgical. It was by design. And now the OTR community that so many African Americans called home is gone. How did that happen?

Once the most serviced community in the state of Ohio, OTR had the highest crime rate, the highest infant mortality rate. So the idea of servicing people, making them whole, obviously does not hold true. You can’t service people and make them whole. But my fear is that people who run the social service system will just want to try it again elsewhere. Social services provide a necessary safety net, but they cannot provide a community with the economic vitality it needs to thrive.

Over-the-Rhine is not the only place where I have seen this happen. In my lifetime, the entire Reading Road corridor died. When I was a kid, I thought Reading Road had everything — movie theaters, bowling alleys, Perkins House pancakes, a big panther overlooking the road. When my family drove down Reading Road, I thought this must be what Las Vegas was like. Years later, the mayor and city manager came to my church to talk about developing parts of Reading Road. And with that — in my lifetime — the entire corridor died.

People continue to be displaced as neighborhoods of families of lower incomes are gobbled up. I look around and see that streets I used to know are gone, as are the people that used to have homes on those streets. It’s painful anytime, but when it happens on my watch, I take it seriously. It’s personal.

And we keep losing ground with local Cincinnati institutions cutting into neighborhoods. Xavier University expanded its campus to where homes of friends once were.10 Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Center has taken homes for its expansion in Avondale.11 A sports team has taken a chunk of the West End with its building of a new soccer stadium.12

Such development efforts are called progress, but too often the progress that we see is also the destruction of a community. And each time, the community being destroyed is coming from the same demographic: African Americans.

When the Greater Cincinnati Redevelopment Authority wants to gobble up Roselawn and nearby Bond Hill, are we to just sit there and eat chicken? Not again on my watch.

A Debt Past Due

“Freeing yourself was one thing, claiming ownership of that freed self was another.”

“Well, that was my great, great grandfather who did that, not me. Why should I have to pay?” say those who oppose anything connected to reparations. And I say, “That was my great, great grandfather who it was done to. And we should be paid.”

Actually, I rarely use the word “reparations.” I prefer to say, “repair the damage.”

Then there are those who say to me, “Damon, haven’t you caught up by now?” And I reply, “How do you catch up to others who had a 350-year head start?”

As I outlined in a preceding section, African Americans spent roughly 100 years following the Civil War fighting legal and illegal apartheid in this country known as “Jim Crow.” Jim Crow m mandated segregation in public facilities, armed services, housing, transit, workplace preferences and public accommodations. As a body of law and practice, Jim Crow institutionalized economic, educational and social disadvantages for the Black community, enshrining into the law the racism of plantations. Redlining, as previously noted, fueled a growing wealth inequality.

And now we have the school to prison pipeline. In 1970, there were 250,000 people in American prisons. Now there are over 2.2 million and too many of them —38% — look like my Black brothers and sisters, yet African Americans only make up 13% of the U.S. population.13 Such mass incarceration is the result of the failed War on Drugs, a term coined by President Richard Nixon in 1971. This “war” was designed to curb illegal drug use. While many will not recognize the name Harry Anslinger, marijuana is now illegal at the federal level because of him. He was a commissioner of the U.S. Treasury Department’s Federal Bureau of Narcotics — our country’s first drug czar. What eventually made marijuana illegal was his one simple message: Black men were smoking weed and having sex with white women.14 That was all that was needed.

This history has left much damage that needs to be repaired— the debt clock never stops. America owes a tremendous debt that has never been acknowledged, let alone paid. The psychological pain and the psychological damage done to African Americans in this country is deeper than any monetary debt, because the damage is mental. The damage is damage to the soul. Repairing this soul damage involves forgiveness, but it is hard to forgive when those who need to be forgiven won’t even acknowledge the pain they have caused.

Actually, there was a time when America acknowledged that it owed a debt to Black people for 244 years of servitude and slavery. The plan to pay that debt was Union General William Tecumseh Sherman’s Special Order 15, which was issued on January 16, 1865. The order called for the massive land redistribution, some 400,000 acres stretching the coastline from Charleston, South Carolina, to St. John’s River in Florida. Each family was to receive 40 acres of tillable ground to “maintain [themselves] and have something to spare.” The plan was developed by Sherman and the Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton, in consultation with 20 Black ministers. Once announced, the plan was quickly acted upon, with one Baptist minister, the Rev. Ulysses L. Houston, leading a thousand former slaves to Skidaway Island, part of the state of Georgia, to set up their own self-governing community.

What happened to Special Order 15? President Lincoln went to Ford’s Theater on the evening of Good Friday to see a play with his wife. We know what followed. John Wilkes Booth, one of the actors, silently made his way up to the balcony where Lincoln was sitting and shot him in the back of the head. The President died the next day. His vice president, Andrew Johnson, a Confederate sympathizer, became President and rescinded Special Order 15. The land that some of the former slaves had already claimed was taken from them and given back to Confederate land holders, the very people who rebelled against the United States.15

Imagine how different race relations in this country would be today if Special Order 15 would have been left standing?

Racism in America is real, and the damage from racism is real. Yet when we ask that the damage be repaired, we are told no. Why? Our Jewish brothers and sisters sought reparations and got it. Our fellow Japanese Americans won reparations. Even Native Americans, whose land was stolen from them, have been given some form of restitution— though hardly what they deserve. It is time now that African Americans receive their compensation.

What Can We Do to Help?

“If you are free, you need to free somebody else. If you have some power, then your job is to empower somebody else.”

In July of 2000, when the Jazz Festival came to Cincinnati, restaurants across downtown closed their doors so patrons had few choices of where to eat. These business owners gave up what would have been an economic boom so as to not serve African Americans. Understand, this was July of 2000. This was not July of 1953. This was not Mississippi. This was Cincinnati, and restaurants were closing their doors to African Americans. That’s when I and others formed the Cincinnati Black United Front. I became its first president.

Interestingly enough, I happened to be downtown with my wife that first night of the Jazz Festival. We were one of the couples pulling on restaurant doors that turned out to be locked. When the first door didn’t open, we thought nothing of it. By the third locked restaurant door, we thought differently. Only later did we find out that 13 restaurants locked their doors that weekend.

We who formed the Cincinnati Black United Front understood that this fight fit into the category that Jesus called “this kind.” In Mark 9:14-29, we find the story of how Jesus healed a young boy possessed by an impure spirit. His disciples tried to heal the boy first but could not. Later the disciples asked Jesus privately, “Why couldn’t we drive [the impure spirit] out?” And Jesus replied, “This kind can come out only by prayer and fasting.”

I had experience with this kind of healing. In the early 1990s, I led my congregation through a period of prayer and fasting to break the hold that crack cocaine had on our Black community.

Now, not quite a decade later, we knew we had to do something different from what had been tried in the past to change Cincinnati from business as usual. In effect, we were responding to the call of Jesus who said, “This time you’ve got to do it differently.”

We started with a boycott of the restaurants. When the local restaurant association asked to meet with us to resolve the issue, I found it interesting that all the people there representing the restaurants were white. I wonder if it ever occurred to them that perhaps that was part of the problem.

Then in November, within a 24-hour period, two Black men — Roger Owensby and Jeffrey Irons — were killed by Cincinnati police. From 1995 to 2001, the only men killed by police in an altercation were Black.16 Since we had already formed the Cincinnati Black United Front, we took up this issue as well. We called the American Civil Liberties Union, and with the help of Ken Lawson, Al Gerhardstein and Scott Greenwood, we filed a class action lawsuit in federal court against the city of Cincinnati for racially biased policing.

Following the lawsuit, we called for a boycott of Cincinnati. Entertainers and conference organizers began to cancel plans to come to the city. Eventually, even the Jazz Festival left Cincinnati and went to Detroit. Our effort had a major economic impact. Fast forward. We ended up with the collaborative agreement, an effort at police reform that has been nationally acclaimed. It was hard fought. Many people were against us — including those on city council, as well as other ministers. Certainly, many white people were against us. Still, we sat at the table and we negotiated. We had pulled every tool that we had out of the Civil Rights toolbox — boycott, lawsuit, protests. We did all three simultaneously.

People often think that we filed the lawsuit in response to the death of another Black man, this one Timothy Thomas, who died on April 7, 2001, after also being fatally shot by Cincinnati police. But we had filed the suit earlier that year.

As much as I am an advocate of nonviolent social change, I understand that were it not for the civil unrest that followed Thomas’ death, it would have been even harder to accomplish what we did. After the three nights of protests, I began receiving phone calls from white people I had never met, people from Cincinnati’s wealthiest neighborhood. “Damon, what can we do to help?” they asked.

I welcome their support, but I say to my Black brothers and sisters, we need to take the lead. Our 400-year journey is over, and it is time for “true emancipation,” that is, self-determination, justice and equity to repair the damage that’s been done.

I don’t want our story stolen anymore nor told by anyone but ourselves.

III. THE PROMISED LAND

Raising Consciousness, Building Wealth

“The philosophy of Black Consciousness therefore expresses group pride and the determination of the Black to rise and attain the envisaged self … At the heart of this kind of thinking is the realization by Blacks that the most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.”

In 2015, I joined a group of city leaders at a press conference that was held at my church. We rolled out a crime prevention plan by calling for community economic development with a $50 million price tag. Why $50 million? That is the amount given to the Cincinnati Center City Development Corporation (3CDC) to create The Banks (a mixed use development district on the Ohio River) and for renovations to the downtown area and the Over-The-Rhine neighborhood.17

“We need the same thing to rebuild the Black community,” we said.

Puzzled, the local media said, “We thought you were laying out a crime prevention plan.”

“We have,” we said.

Economics and building community wealth have been my focus of recent years, that is, community economic development (CED). This is a process that engages a community in its own economic vitality. In that sense, CED is different from economic development. How does it differ? The renovation of Findlay Market in Over-the-Rhine is a good example of economic development that lacked a crucial component — community.

In 2004, the city of Cincinnati completed a $16 million face lift of its historic Findlay Market.18 The result was beautiful. But for the people who live in the neighborhood surrounding Findlay Market, these renovations meant nothing. The people who live in the community did not do the construction work. They did not have stalls in the market. Instead, they just saw $16 million being poured into their community while they still lived in poverty. That is economic development. Community economic development says if $16 million is being poured into a community, then those dollars need to uplift the people who live here. Those who live in the community actually need to do the work and receive the benefits. Otherwise it is just economic development for the benefit of someone outside the neighborhood.

Traditionally, in this country, the effort has been toward community and economic development. We need to remove the “and.” It simply needs to be community economic development. With the “and” in place, the community is serviced to the point where it becomes a service community, that is, a community dependent upon the services provided by others. It focuses on what a community lacks.

When economic development becomes separate from community development, developers are able to come in, buy the land and make renovations with no understanding or appreciation of what it may mean to the community. Economic development builds wealth for the developers. If a community is engaged in its own economic vitality, which is what the CED process is all about, there is no way that a government agency can put $16 million in an enterprise, as we saw with Findlay Market, and not uplift the people who live there.

Community economic development is a key component in Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD). ABCD builds community wealth by recognizing that surrounding people with social services does not make them whole. It if did, Over-the-Rhine would have been the best community in America, instead of being ripe picking for developers.

One aspect of ABCD is Individual Development Accounts (IDA). IDAs are a type of savings account to help individuals of low income achieve financial stability and long-term self-sufficiency by building up their assets. IDAs are used to save money to start a business, pay for education or buy a home.

Another aspect of ABCD is community funds. A community fund is, quite simply, one in which the community has invested. It is a type of investment fund where those most affected are the first contributors.

In order to be a member of the fund, you have to be a resident of the community or own a local business in the community. You have to be a stakeholder. Those outside the community are welcome to contribute to the fund, but they do not have a vote on how the money is to be used. Only residents and local business owners have that right. In other words, any interest from investors living outside the community must be secondary to the life and dreams of a community. Outside resources are needed and necessary — hence our request for the same amount of money given to the developers of Cincinnati’s city center. But the sources of these outside resources need to be the second investors.19

In order for community development to be successful, everyone in the community needs to contribute something (or, at the very least, needs to be encouraged to contribute). That is because everyone has something to give. Everyone has a gift. And it is imperative, not only to our own lives and the lives of our families, but for the life of the Black community, that residents and business owners each try in their own way to make things better.

Effective organizing is key to the success in establishing a community fund. But there is another component that is equally important. People have to believe that they have the power to own, possess and develop their own community. That is the core challenge in building wealth in a Black community. We African Americans need to believe in ourselves. We need to use the gifts and assets and resources that we already have and build upon those. Then we need the courage to move forward, to possess and redevelop the land for the benefit of our community.

This is all about building a strong, healthy Black community. We can do this by raising consciousness and building capital — we must do both. If we build Black wealth without consciousness, there is no benefit to the community. If we build Black consciousness without wealth, we are just talking a good game — and we don’t have time for that.

I see the Black community setting a table for itself. We African Americans are having a dinner. There are some extra seats to which we can invite our white brothers and sisters, but they don’t get to tell us what to cook.

Black residents need to reclaim their own community.

Sinking Roots Deep

“Not everything can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

One of the things that hampers poor communities, a Black community in particular, is that every 20 to 25 years the people are uprooted. True community economic development is not possible with such displacement. A long-term, stable, local community is absolutely essential for wealth building. Displacing people every generation, scattering them to different parts of a city, destroys the relationships that make for a strong, healthy community.

Displacement happens when suddenly a community, their streets, businesses and homes, become “the new thing.” Those who were not part of the community move in and replace those who lived there. We saw that happen in Over-the-Rhine. We don’t want that to happen again. So where do we start? Ownership. Black ownership of the land where Black homes and businesses sit, followed by taking ownership of an economic sector— a co-created, co-produced enterprise.

The critical factor for individuals who are trying to advance themselves is to find a niche where they can fit in, belong and succeed. The same is true for a community. The Black community needs an economic sector to claim as its own, much as Americans of other minority groups have done.

Other minority groups, smaller than the Black community, are doing well, relatively speaking, because they control certain sectors of the economy. And they work together. White Americans often speak of rugged individualism, pulling oneself up by one’s bootstraps, but that is not how it works. It is certainly not how Asian Americans or Arab Americans do it. They work together, supporting one another and, as a result, wind up controlling different segments of the economy.

Korean Americans control the Black hair care market in America.20 Arab Americans own the corner stores and gas stations.21 Indian Americans own motels throughout the South.22 African Americans don’t have that same claim to a particular economic sector. Certainly we have our own barber shops and funeral homes — as well as churches. That’s because most Black men want their hair cut by another Black man. And Blacks want to be buried by other Blacks. And if Black people go to church, they usually attend a church where the membership is predominantly Black. But none of these are enterprises that serve other racial groups.

In other words, there are smaller groups than the Black community who control major economic sectors in our national economy. African Americans cannot point to one economic sector that it has any major control of. That needs to change.

We have installed 352 solar panels on the grounds of our church with the aim of reducing our energy costs. We are now able to provide cleanly-sourced energy throughout the facility. In the process, we learned. We look to share our knowledge with our community toward the end that solar power could become a niche the Black community can own. I believe that every home in the Black community surrounding Roselawn needs to have solar energy. Think of the savings in the long term for those households. When people come to my church with a financial need, it is because they have fallen behind in rent or cannot pay their electric bill. If the Black community begins to control even part of the solar power industry, we African Americans will have made a giant step forward.

Part of this work is to create a narrative that is conceivable, believable, achievable — what I call CBA. It is a story that says a strong Black community must take root and lift up the lives of all African Americans. It is a story where education is valued and where there is a deep sense of and respect for community. When a community is destroyed, those values are lost.

The uprooting needs to stop.

Self-Determination

“If you’re always trying to be normal, you will never know how amazing you can be.”

In the late 1990s, there was initial excitement in Cincinnati over the success of an application for federal Empowerment Zones.23 Empowerment Zones are designated areas where employers and other taxpayers qualify for special tax incentives to reduce unemployment and generate economic development. These initiatives met with limited success, in part, because the community component of these efforts had limited input from the community and its major stakeholders. When initiatives are institutionally owned, and not community owned, there is no empowerment of the community, and therein lies the problem.

The Empowerment Zones did nothing to create a strong sense of community, particularly in Black neighborhoods. As when a social service agency receives a grant, its leaders see solutions on the horizon. But without community, there is no solution.

Such programs are supposed to serve the needs of a community, yet the leaders of these efforts have nothing to do with the community they are trying to serve.

Agencies are not going to be the salvation of poor people in Cincinnati — or any city for that matter. What is needed first is a strong community. We need to shift from servicing a community to nurturing the inherent intelligence of a community. We need to acknowledge, affirm and activate the inherent resources and gifts of people and the opportunities that can be found within their community. It is activating versus organizing. It is cultivating. There is where the salvation of African Americans lies.

We who identify as Black can make things better for our community. We can do this through what Marshall Ganz calls a “stream of effective strategy” in his book Why David Sometimes Wins: Leadership, Organization and Strategy in the California Farm Worker Movement, where motivated and knowledgeable individuals create venues for learning by others.24

Building a sense of community is the “first intimate circle” where the focus needs to be. It doesn’t mean that in the outer circles there’s not government support and institutional support — because that is needed too. But first, we African Americans have to build that inner circle of self-determination that says we’re going to do this against all odds, that says we’re going to do this with or without help. Yes, we have to tackle and fight the oppressive nature of the system, but if we don’t bring the community together, if we don’t build a sense of community, which is lost right now, none of the rest of that matters.

That’s what the earlier efforts to help the Black community showed me. Failure was the result when we did not build community first. I am working with a group now toward that end— the Community Economic Advancement Initiative (CEAI). The focus of CEAI is to develop small businesses to build wealth and to create sustainable housing within the Black community.

As noted, the key to building wealth in the Black community is through home and land ownership and the creation of small businesses. It’s about passing wealth down to future generations to build a strong Black economy. This is different from job training. It is different from increasing the numbers of people going to college. And it certainly is different from feeding and clothing people. Our organization has purchased four acres of land where we will build houses that are solar powered — it’s time to get these things done.

As land becomes available, I look for us to buy it. “Take the land,” God told Joshua. In today’s terms, that means African Americans need to take the economic future of their community into their own hands. The time for waiting for it to happen by any other means is over.

It is all about self-determination.

I wrote earlier how African Americans wrestle with an overriding sense of inferiority. We wake up to it. But I say it is time to wake up from it. It’s time to rise up.

While there have been and continue to be grave injustices in the lives of Black people living in this country, we cannot stay focused there. It is time for African Americans to control their own economies, not for themselves but for their community, which in turn will provide ongoing support to their own lives.

True Emancipation

“If the Emancipation Proclamation was authentic, you wouldn’t have a race problem.”

At my church, we followed a program developed by D. L. Williams that involved 40 days of no frivolous spending.25 Those who participated learned that there are things that they really don’t need in life, and they were able to start saving money. The testimonies at the end of the first year of the program were amazing. People who never had any savings had $500 put away— and they felt good about it. People were paying off credit cards. They were beginning to release themselves from toxic debt. The program calls for people to work together in small groups in support of each other. Some of our groups have been together for years and have built strong bonds with one another. My vision is to build something similar on a community level. We will invite anyone in the community to be a part of it.

It is a way to build the will in the Black community to do for itself. It will be a way to begin the reconstruction of common relationships. Added to real economic justice, these two components can go a long way toward improving race relations.

Today in America we are seeing a resegregation. This change is happening not by law but by choice. Resegregating does not mean that desegregation was not necessary — it was. Barriers needed to be broken down. Laws needed to be changed. That was the work of desegregation. But integration is totally different from desegregation, and African Americans have paid a price for that. Resegregation is what is needed now and is something that the Black community can accomplish by leading the way in repairing the breach.

This does not mean the Black community resegregate to the point of exclusion of those of a different race or ethnicity. It just means that resegregation is something that our Black community needs to do for itself right now to build for the future. And while we need to listen to the older generation to understand what has been lost in just a lifetime, we absolutely need the voice and drive and energy of the younger generation in this effort. So part of the work is to create a mutual connection between these two generations.

The older generation has the vision of a strong Black community because they lived it. But the younger generation is going to be on the forefront of rebuilding what once was and re-imagining what could be. Both generations need to embrace the communal history of African American people. Both need to recognize that the work is more than landing a job. It is about restoring, rebuilding the whole, which is the hearts and minds of a people. It is about forging a connection that honors, respects and holds all of us responsible.

When I went to Over-the-Rhine thirty years ago, four older, primarily African-American women— Linda Brock, Julie Fay, Marva Royal and Fatimah Shabazz — took me under their wing. They were the organizers. Just as these older women mentored me, I look to serve in a similar capacity to members of the younger generation. I don’t want to proscribe — to set limits or prohibit — but rather prescribe in the sense of a recommendation for a course of action to follow. I want to know what skills and abilities — and wisdom— young people see themselves possessing to help others make a difference. I want to ask them if they collectively see themselves as actors with a major role to play in building up the Black community. My only charge to them would be to use those skills and ability and do their best not to leave anybody behind.

Historically when African Americans did build a strong, viable community, it was destroyed. We cannot let that happen anymore. There needs to be a movement of people, made of African Americans and white Americans who care, people who are fighters for social and economic justice. This new work is about equity. And because African Americans have been the most damaged from 400 years of injustice, they are the ones who need to lead the way. It’s that simple.

I have told friends if resegregation is the direction we are headed, then let’s make it work through economic empowerment and self-determination. Making resegregation work is essentially about the task of reparation. Let us be role models for our children, showing them how a Black community can be strong and healthy and whole. Let’s make resegregation work. Let’s get to it.

III. THE ROAD MAP

“Commit to the Lord whatever you do, and he will establish your plans.”

In the preceding pages, I laid out a vision, a course of action that I believe God is calling African

Americans to implement. This action is to be built upon community economic development, whereby the people themselves create economic opportunities that improve social conditions, particularly for those who are most disadvantaged. To be effective, this community economic development must be rooted in local knowledge and led by the community members themselves.

Following is an outline of four key components of effective community economic development.

Community Education Plan

Today’s schools are failing Black children of low income households, and Black families recognize this. Indeed, studies have shown that children from low income households are less likely to succeed academically than those children whose family income is middle class or higher.26 The difference stems not from a lack of ability, but from a lack of resources both within the home and the school— a critical fact to note, as I said earlier.

To address this challenge, we need to provide supplemental schools within the Black community to help young African American students achieve at the same level or higher as those students from households with higher income. Such community-based schools can fill the major gaps left by mainstream education.

These supplemental schools are to utilize basic teaching resources found within the knowledge of the residents of the Black community and the educational opportunities of local associations.

Community Health Plan

The disparities between the health of African Americans and white Americans are well documented. These disparities must and can be addressed by the practice of good self-care by African Americans, along with a demand for equity across the board when it comes to health care for all African Americans.

Just as supplemental schools are to utilize basic teaching resources rooted within the knowledge of residents within the Black community, health care needs to be led by Black health care professionals through neighborhood clinics and health education, working in partnership with the wider health care community.

Community Safety Plan

The amelioration of poverty in Cincinnati is inextricably tied to safety in communities. Likewise, safety needs to be in the hands of the community, not the police. About 70% of the city of Cincinnati’s budget is allocated for public safety, that is, police, fire and emergency medical services.27 Yet, African American residents in many communities do not feel safe. The fear of violent crime and, in some instances, the fear of law enforcement is a daily reality for the most vulnerable in our society.

There are five principles that need to influence the planning for safety and well-being of every community, but particularly the Black community. The first is a demonstration of commitment at the highest level. This commitment needs to be followed by the next three principles, which are risk-focused, collaborative and asset-based. The final principle is that the outcomes must be measurable.28 Everything done in the name of community safety planning must adhere to these five principles for the greatest positive effect.

Community Energy Plan

Energy costs are a major component of the operating expenses for a household and can impose a significant burden on families of low income. A community energy plan provides the pathway for the Black community to strengthen local economies, reduce current and future energy costs and create jobs by investing in smarter and more integrated approaches to energy use at the local level.

A sound community energy plan will increase the likelihood of new high-tech investments in the Black community. The money saved from reduced energy costs can be recirculated to further the local efforts of a community energy plan. Or, those dollars can flow directly back into the Black community for other needs. Those dollars can be a source of job creation. And finally, by creating opportunities for local energy cost savings, a community energy plan can also increase the affordability of housing and contribute to strong and resilient local Black economies.

Conclusion

These plans, and others that have and will come from the Black community, are blueprints for self-sufficiency, wealth creation and self-determination. They are a part of the “next 400 years.” It is imperative that those of us who stand on the shoulders and live in the shadows of the great men and women of the past plot a dynamic course for the ones coming after us. It is time for African Americans to cash the check that Dr. King spoke about at the March on Washington when he said, “It has come back stamped insufficient funds.” And African Americans are the ones who are to make sure that the check is good.

These pages prescribe a way forward as never before attempted in this land. And the time is now to show that we, my Black brothers and sisters, can succeed. It is up to us to take our destiny into our own hands, a destiny that in prior centuries we were forbidden to claim. That is no longer the case. We need to “claim the land,” as God commanded. We need to be our own Joshuas. We need to show all Americans how this great nation can live into its promises for all.

© 2021, Damon Lynch III.

RESOURCES

Books

Alexander, Michelle. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: The New Press, 2012.

Anderson, Claud. Black Labor, White Wealth: The Search for Power and Economic Justice. Bethesda, MD: PowerNomics Corporation of America, 1994.

Andrews, Kehinde. Resisting Racism: Race, Inequality, and the Black Supplementary School Movement. London: Institute of Education Press, 2013.

Curnutte, Mark. Across the Color Line: Reporting 25 Years in Black Cincinnati. University of Cincinnati Press, 2019.

DeGruy, Joy. Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome: America’s Legacy of Enduring Injury and Healing. Milwaukie, Oregon: Uptone Press, 2005.

Robinson, Randall. The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks. New York: Plume, 2001.

Rothstein, Richard. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. New York: Liveright Publishing, 2017.

Stevenson, Bryan. Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption. New York: Random House, 2015.

Organizations

Collective Empowerment Group

The Collective Empowerment Group (CEG) advocates the church as an effective vehicle to bring about economic empowerment and wealth building. A Christian ministry, CEG draws together leaders from faith, business and public service sectors to develop and enhance economic empowerment strategies for its members and the communities they serve. Learn more at cegcincinnati.com.

Common Good Collective

Established in 2019, the Cincinnati Common Good Collective was forged to provide a place where activists come together to build community. Learn more at commongood.cc.

Community Economic Advancement Initiative

The Community Economic Advancement Initiative is committed to the sustainable model of asset-based community development (ABCD). CEAI recognizes that a community already possesses the gifts, skills and passions needed to create a satisfactory and stable quality of life across generations. The work of CEAI is to harness those capacities for the community benefit. Learn more at ceaicincy.org.

Restore Commons

An initiative of Peter Block and friends, Restore Commons curates ways of thinking about and practicing the common good. It is designed to be a gathering place for stories and radical ideas strong enough to build the social capital and the engaged community required to restore the common good. Learn more at restorecommons.com.

NOTES

1 Melissa Brown, “An Era of Terror: Montgomery family remembers father’s lynching, legacy,” Montgomery Advertiser, April 25, 2018. See also The Elmore Bolling Foundation, http://www.bollingfoundation.org/home.html.

2 Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New York: Liveright, 2017), vii-xvii.

3 Kriston McIntosh, Emily Moss, Ryan Nunn and Jay Shambaugh, “Examining the Black-White Wealth Gap,” Brookings Institute, February 27, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/02/27/examining-the-black-white-wealth-gap.

4 McIntosh et al, February 27, 2020. See also Janelle Jones, “The Racial Wealth Gap: How African-Americans have been shortchanged out of the materials to build wealth,” Economic Policy Institute, February 13, 2017, https://www.epi.org/blog/the-racial-wealth-gap-how-african-americans-have-been-shortchanged-out-of-the-materials-to-build-wealth.

5 Noah Kirsch, “Members of The Forbes 400 Hold More Wealth Than All U.S. Black Families Combined, Study Finds,” Forbes, January 14, 2019.

6 Randall Robinson, The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks (New York: Plume, 2000), 209-214.

7 Robinson, 214-216.

8 Alyssa Konermann, “25,737 People Lived in Kenyon-Barr When the City Razed it to the Ground,” Cincinnati Magazine, February 10, 2017.

9 John Oseid, “Over-The-Rhine: Cincinnati’s historic neighborhood hums again,” Forbes, June 10, 2019. See also Elaine Glusac, “36 Hours in Cincinnati,” The New York Times, August 17, 2017.

10 Ben L. Kaufman, “XU Plans $20 Million Expansion,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, February 2, 1984.

11 Mark Curnutte, “The Long Hard Road: Change comes with a cost,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, September 22, 2019.

12 Sharon Coolidge, “FC Cincinnati Scoops Up More Land for West End Stadium Development.” The Cincinnati Enquirer, November 15, 2019. See also Chris Wetterich, “FC Cincinnati Signs Purchase Option for Large Number of West End Properties,” Cincinnati Business Courier, January 23, 2018, and “School Board Approves West End Land Sway for FC Cincinnati Stadium,” Cincinnati Business Courier, April 10, 2018.

13 Federal Bureau of Prison, https://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/statistics_inmate_race.jsp.

14 Laura Smith, “How a Racist Hate-monger Masterminded America’s War on Drugs,” Timeline, February 28, 2018, https://timeline.com/harry-anslinger-racist-war-on-drugs-prison-industrial-complex-fb5cbc281189.

15 Henry Louis Gates Jr., “The Truth Behind ’40 Acres and a Mule,’” The African Americans: Many rivers to cross, https://www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/history/thetruth-behind-40-acres-and-a-mule.

16 Dan Klepal, “‘Fifteen’ Becomes Activists’ Rally Cry,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, April 15, 2001.

17 Ken Alltucker, “3CDC: Group now looks ahead,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, July 4, 2004.

18 Anna Guido, “Findlay Market: Feeling about renovation mixed,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, April 2, 2004. See also Dan Monk, “Merchants Finding Retail Space Scarce at Findlay Market,” Cincinnati Business Courier, November 12, 2010.

19 Boston Ujima Project. https://www.ujimaboston.com.

20 Emma Sapong, “Roots of Tension: Race, hair, competition and black beauty stores,” MPR News, April 25, 2017.

21 “Power of the Purse: Middle Easterners and North Africans in America,” New American Economy Research Fund, January 27, 2019, https://research.newamericaneconomy.org/report/power-of-the-purse-middle-easterners-and-north-africans-in-america.

22 Yudhijit Bhattacharjee, “How Indian Americans Came to Run Half of All U.S. Motels?” National Geographic, September 4, 2018.

23 Lisa Donovan, “$3M to Cincinnati Inner City,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, January 14, 1999.

24 Marshall Ganz, Why David Sometimes Wins: Leadership, Organization, and Strategy in the California Farm Worker Movement (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 8.

25 D.L. Williams, The 40 Day Financial Fast: A Paradigm Shift Towards Financial Freedom (2017), https://www.amazon.com/40-Day-Financial-Fast-Shifting-Paradigm/dp/0692916547.

26 Katherine Michelmore and Susan Dynarski, “Income Differences in Education: The gap within the gap,” Econofact, April 20, 2017, https://econofact.org/income-differences-in-education-the-gap-within-the-gap.

27 Chris Wetterich, “As City Council Scrutinizes Budget, Hundreds Plan to Pack Hearings, Cincinnati Business Courier, June 16, 2020.

28 Sylvia Jones et al, “Community Safety and Well-being Planning Framework: A shared commitment in Ontario,” Ontario Ministry of the Solicitor General, September 14, 2018, https://www.mcscs.jus.gov.on.ca/english/publications/MCSCSSSOPlanningFramework.html.

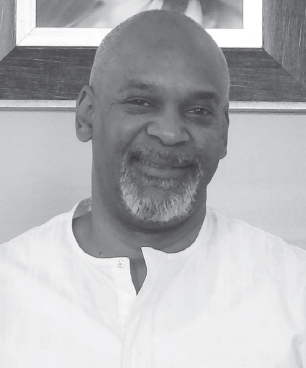

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

For 30 years, the Rev. Damon Lynch III has served as the senior pastor of New Prospect Baptist Church, now located in the Cincinnati neighborhood of Roselawn. He also serves as president and CEO of Community Economic Advancement Initiative (CEAI), while championing for other community organizations, including the Collaborative Agreement Refresh, the AMOS Project, the Opiate Coalition of Hamilton County, Strive Partnership, the Common Good Collective and more.

For 30 years, the Rev. Damon Lynch III has served as the senior pastor of New Prospect Baptist Church, now located in the Cincinnati neighborhood of Roselawn. He also serves as president and CEO of Community Economic Advancement Initiative (CEAI), while championing for other community organizations, including the Collaborative Agreement Refresh, the AMOS Project, the Opiate Coalition of Hamilton County, Strive Partnership, the Common Good Collective and more.

As a founding faculty member of the Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD) Institute at DePaul University, Lynch has conducted workshops and seminars throughout the United States.

He holds a Bachelor of Science degree from Cincinnati Bible College.

For more information on the Becoming Joshua movement and how you can support it, contact:

The Rev. Damon Lynch III, CEO Community Economic Advancement Initiative

1237 California Ave.

Cincinnati, OH 45237

513.429.2158

ceaicincy.org